Docker for Dummies

Published:

Docker is a useful tool widely used today to facilitate software development and shipping code. This article covers a comprehensive overview of docker containers and how to use them.

Introduction

A container is a package application with all the necessary dependencies and configurations for development, deployment and shipping. Containers are portable, and are hosted on their own private repository. DockerHub is a public repository for docker containers, and is usually the starting point for development.

With containers, we can set up an isolated environment packaged with all the needed configuration and dependencies, and uses one command to install the app. This makes distributing a uniform development environment much easier. This also allows us to run multiple versions of the same application without encountering any version conflicts (i.e. running postgres 9.6 and 10.10 at the same time)

Docker vs Virtual Machines (VMs)

Virtual Machines are made up of 2 layers running on top of your machine hardware:

- Application (filesystem, libraries etc.)

- OS Kernel

Dockers containers only contain the application layer. It uses the local machine’s hardware and OS kernel to run its programs. As a result, docker containers are:

- Much smaller (~mb) in size as compared to VMs (~gb)

- Starts and runs much faster than VMs (more lightweight)

- Docker containers can only be run on a specific OS since kernels are OS specific :(. VMs can run on any OS.

Installation

The Docker documentation provides an installation guide for a variety of OSes.

Architecture of a Docker Container

A docker container is made up of a stack of layers of images, with its base image being some sort of linux distribution. It is important for this image to be small (e.g. alpine). At the top would be the application image (i.e. postgres).

Docker image: an application package and its dependencies/configurations/start scripts etc. A docker image is a static artifact that can be moved around.

Docker container: An image that has been pulled and is running on a machine, creating an isolated application environment.

A docker container can be pulled from a repository using docker pull <image_name>:<image_tag> or docker run <image_name>:<image_tag>. The <image_tag> is an optional parameter. Using the run command automatically pulls images not installed locally and runs it.

Tag: The docker tag refers to its image version.

A docker container has a port bound to it to allow communication with the application running in the container, and has its own isolated virtual filesystem.

Ports

Multiple containers can run on your host machine, each bound to a port on the host machine. Each container must be bound to an open port on the host machine (i.e. no sharing ports with other applications, or conflicts will arise). Ports can be specified when running the docker container using the docker run command. More information can be found in the section below.

Dockerfile

The dockerfile is the basic building block for docker images. It is a simple text file (no file extension) with instructions and arguments, and works similar to a setup file. Docker can build images automatically by reading the instructions in a dockerfile. The syntax of the file is as follows:

# Comment

INSTRUCTION arguments

A dockerfile may look something like this:

FROM some-base-image

COPY some-code-or-local-content

CMD the-entrypoint-command

RUN npm install

For a better look at what a Dockerfile looks like, see this Dockerfile for the official pytorch container. Each instruction in the dockerfile adds an extra layer to the docker image. Instructions should be consolidated to minimize the build’s performance and runtimes.

It is not always necessary to write your own dockerfile. They can be autogenerated if you are creating the container manually (i.e. through pull , run and other commands). However, using a dockerfile may speed up image creation and facilitate environment distribution. To avoid security breaches, it is also best to run commands through the dockerfile as a non-root user.

Below are an overview of the Dockerfile instructions. See the official documentation for more usage details.

| Dockerfile Instruction | Explanation |

|---|---|

| FROM | To specify the base image which can be pulled from a container registry (DockerHub, GCR, Quay, ECR, etc) |

| RUN | Executes commands during the image build process. |

| ENV | Sets environment variables inside the image, available during build time as well as in a running container |

| COPY | Copies local files and directories to the image |

| EXPOSE | Specifies the port to be exposed for the Docker container. |

| ADD | More feature-rich version of the COPY instruction (allows copying from source URL and supports tar file auto-extraction into the image). However, COPY is recommended over ADD. To download remote files, use curl or RUN. |

| WORKDIR | Sets current working directory |

| VOLUME | Create or mount the volume to the Docker container |

| USER | Sets the username and UID when running the container. Can be used to set a non-root user. |

| LABEL | It is used to specify metadata information of Docker image |

| ARG | Is used to set build-time variables with key and value. |

| CMD | Execute a command in a running container. There can be only one CMD (only last CMD is applied if there are many). It can be overridden from the Docker CLI. |

| ENTRYPOINT | Specifies commands to be executed when the container starts. Defaults to /bin/sh -c. In the CLI, use the –entrypoint flag to override. |

Docker Build Context: The docker host location where all the code, files, configs and Dockerfile for building the container live. It is possible to have the dockerfile be in a separate repository to the build context. Ideally, the build context should be kept isolated from any unrelated files to avoid unwanted files bloating the docker image.

.dockerignore File

Similar to the .gitignore , Docker also has its own .dockerignore file, which basically works the same way, excluding the listed directories when the CLI is sending the container’s context to the docker daemon. This prevents unnecessarily sending large or sensitive directories to the daemon and potentially adding them to images using ADD or COPY.

A .dockerignore file may look like this:

# comment

*/temp*

*/*/temp*

temp?

Docker Repositories

There are two types of docker repositories: public (e.g. DockerHub) and private. Docker repositories store container images. Similar to a github repo, members have push/pull access and can be assigned other permissions. Image tags and other details can also be viewed.

The docker search <image_name/username/description> command can be used in the docker CLI to search the official DockerHub registry for images.

Unlike github however, deploying a private docker repository is not so straightforward. The Docker Registry will need to be installed on the host server, and Nginx will have to be set up. Essentially, it is similar to setting up a database or web server. This guide provides detailed instructions on how to set up a private server on Ubuntu 22.04. After setting up the repository, CI tools can also be use to automate pushing to a private registry directly.

An image is stale if there has been no push or pull activity for more than one month. A multi-architecture image is stale if all single-architecture images part of its manifest are stale.

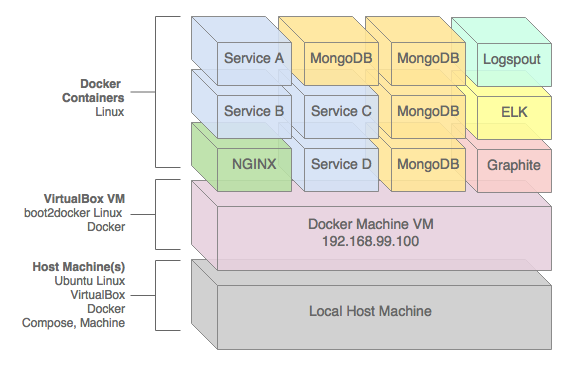

Docker in a Tech Stack

Docker falls under the DevOps category in a tech stack, facilitating better management of development environments and application deployment. Below is a sample diagram of a possible tech stack with docker containers.

Sample tech stack with docker containers (source)

Sample tech stack with docker containers (source)

Docker Commands and Actions

In this section, I go through several key docker CLI commands. More information can be found on the docker documentation page.

Running a Docker Container

Docker containers can be created and run using the docker run -p<host_port>:<container_port> <image_name/image_id>:<image_tag> command. As mentioned previously, the <image_tag> parameter is optional. The -p flag allows you to specify the port binding between the host machine and the docker container. As a rule of thumb, this should always be used when running containers to avoid port conflicts.The -d flag can be used to run the container in detached mode, so the terminal can still be used to run other commands. The container name can also be set with the --name flag. If not specified, an autogenerated name will be set, which can be viewed using the docker ps command.

To check active containers on your machine, you can use the docker ps command. To check the docker running history, use the -a flag.

To stop a running container, you can use the docker stop <container_id> command.

Running Multi-container Applications

Docker compose is a tool for defining and running multi-container docker applications. With compose V1, a YAML file was required, describing all the docker services to be started together. Docker compose V2 is included with docker desktop, and is now a 3-step process:

- Define the

Dockerfile - Define you application’s services in

docker-compose.yml - Run

docker compose up

A service’s definition includes the configuration to be applied to each container, similar to the parameters used when running docker CLI commands such as run or build . Dockerfile options are applied by default, and do not need to be duplicated in the compose file.

A range of docker services can be defined in the dockerfile, such as:

runnetwork createvolume createbuildand dependencies between services can also be specified. Dependencies are started and stopped in the order specified in the compose file.

A docker-compose.yml file may look like this:

services:

web:

build: .

depends_on:

- db

- redis

ports:

- "5000:5000"

volumes:

- .:/code

redis:

image: redis

db:

image: postgres

healthcheck:

test: "exit 0"

| If you are migrating from compose V1 to V2, it may be useful to take a look at this guide. |

Finding Open Ports on Your Device

There are various ways to find out which ports are open on your device if you are not sure which port to use. In general,

- Well Known Ports: 0 - 1023

- Registered Ports: 1024 - 49151

- Dynamic and Private Ports: 49152 - 65535

On Windows, you can use the netstat CLI tool, which shows protocol statistics and the current TCP and IP network connections. Other flags can be specified to filter the output:

-adisplays all connections and listening ports.-bshows all executables involved in creating each listening port.-oprovides the owning process ID related to each of the connections.-nshows the addresses and port numbers as numerals.

There are two commands that can be used to identify open ports:

netstat -ab: Look for the port number you want to use and check that is states LISTENING, indicating it is open.netstat -aon: Look for the port number you want to use (under the Address column) and check that its state is LISTENING. To confirm the port is open, use the PID to find the serve bound to the port by going to task manager -> Services -> Check which app uses the port in the description and check its status.

On Linux, there are several methods:

sudo netstat -tulpn | grep LISTENdisplays open ports, with the additional flags-tfor TCP and-ufor UDP portssudo ss -tulpnsudo lsof -i -P -n | grep LISTEN- Or using the

nmaptool,sudo nmap -sU -O 192.168.2.254lists open UDP portssudo nmap -sT -O 127.0.0.1lists open TCP ports

Restarting an Existing Docker Container

When docker containers are created from images using the docker run command, the containers are saved with a unique container ID. We can restart previously created (and then stopped) containers using the docker start <container_id/container_name> command. This allows you to start a container with all the same configurations (i.e. port numbers, container name etc.) that were previously specified.

Building a Docker Image

Docker images can be built from a dockerfile using the docker build <dockerfile_path> command. This builds images from a Dockerfile and a ‘context’, which is the set of files located in the specified path or URL. The -t flag can be specified to tag the image. A single image can have multiple tags:

- Stable Tags: Tag is constant, but the image content may change. Pull using the same tag name.

- Unique Tags: A unique tag is used for each image. There are different systems of tagging, such as date-time, build number, commit ID etc. In production, the Semantic Versioning tagging system is often used.

Viewing and Cleaning Docker Images

A docker image may be small, but can add up over time, taking up significant space on your disk drives. The docker images command can be used to view all docker images currently on your local machine.

To delete unused, dangling docker images from your machine, the docker system prune command can be used. The --filter flag can be used to specify a filter value (i.e. label=<key>=<value>) and the -a flag can be specified to remove all docker images.

Debugging a Docker Container

To check active docker containers, use docker ps.

Upon encountering issues, you can access the container logs with the docker logs <container_id/container_name> command.

To gain access to a container’s terminal, we can use the docker exec -it <container_id/container_name> /bin/bash command. This allows you to log in to the virtual filesystem in a container as a root user. To exit, use the exit command.

Fixing an Incompatible Docker Image

Sometimes, we want to run the docker on a different machine, but we may only have access to machines which are a different OS than what was intended for the container. This is a particularly frustrating issue.

Windows 10 and later added support for Hyper-V virtualization. Hence, for machines running on these OSes, it is possible to run linux docker images using the docker CLI or desktop GUI tool, provided Hyper-V is enabled (in the bios). Simply running docker run -it <container_name> should pull and run the container image, and give you access to its terminal. For a more detailed guide, see this article.

For other machines, in general, there are 2 workarounds:

- Redo the docker image setup for the OS you want to run it on

- Use a VM running on Hyper-V (e.g. MobyVM, Oracle VirtualBox)

Docker Network

Docker containers become a powerful tool since multiple containers can be run and connected to each other, or even non-docker workloads, allowing a higher level of application isolation. The typical docker network is a bridge network, with the host machine acting as the bridge entity between docker containers and the outside world (i.e. internet/local network etc.). NAT and host networking is only supported on Linux host machines.

Docker provides native support for 3 types of networks: bridge, host, none. However, in the case where these network structures are unapplicable, user-defined network plugins (i.e. overlay, macvlan, ipvlan etc.) can be used. By default, the docker network drivers creates a set of docker networks following the Bridge protocol.

To view networks and their scopes, use the docker network ls command. More information on docker network commands can be found using docker network help, and also on the official documentation.

To connect a container to a network, use docker network connect <network_name> <container_id/container_name> . To disconnect, use docker network disconnect <network_name> <container_id/container_name> . To check if containers are attached to the network, use docker network inspect <network_name>.

Bridge Driver

The bridge is the default network. All newly started containers will connect to the default bridge network automatically. Containers on a bridge network communicate through IP address. Every time a container is run, a new IP address is assigned to it. This works fine for local development or with CI/CD, but is not sustainable for production. The default bridge protocol will also allow containers communication access to all containers on the network, even if they are unrelated, which could be a security risk. Custom bridge networks can be defined to mitigate this issue, but it is still not recommended for production.

Use When:

- Containers need to be run isolated and communicate with each other

- You are running applications in test/dev mode

When using a bridge network, containers inherit the DNS settings from the host. Custom host records can also be added to the container using the --dns flag.

Host Driver

Host drivers use the networking provided by the host machine. This removes the isolation between container and host by allowing the container to be available on the host port it is bound to, on the host’s IP address. Host networking is only available on Linux hosts, however.

Use when:

- You have a linux machine

- You don’t want to use Docker’s networking protocol

Use the docker run --rm -d --network host --name my_nginx nginx command to start an Nginx image and listen to port 80 on the host machine.

Port 80 is a well-known port used for internet communications through HTTP.

None Driver

The none driver does not attach any containers to any network, so containers are completely isolated from any communications.

Use when:

- You want to disable networking on a container

Overlay Driver

The overlay driver supports multi-host network communication, such as Docker Swarm or Kubernetes. The overlay driver creates a distributed network among docker daemon hosts, and sits on top of the host-specific networks, allowing connected containers to communicate securely when encryption is enabled. Docker will handle the routing of packets to and from the docker daemons and destination container.

Use docker network create -d overlay <network_name> to create an overlay network for Docker Swarm. If you want to create an overlay network for standalone containers instead, use docker network create -d overlay --attachable <network_name>

macvlan Driver

The macvlan driver connects docker containers to the physical host network directly. A MAC address needs to be assigned to the container to make it appear as a physical device on the network. The docker daemon then routes traffic to containers via their MAC address.

Use when:

- You are running legacy applications (that are built to be connected directly to the physical network)

- You don’t have too many containers running (to avoid VLAN spread, where your IP address is oversaturated with unique MAC address, thus damaging your network)

- Your application can’t use other network drivers

To create a macvlan network, use docker network create and specify the subnet, gateway and parent like so:

docker network create -d macvlan \

--subnet=172.16.86.0/24 \

--gateway=172.16.86.1 \

-o parent=eth0 pub_net

IPvlan Driver

The IPvlan driver gives users complete control over IPv4 and IPv6 addressing. On linux, this is extremely lightweight since they are associated to a linux ethernet interface/sub-interface, rather than a bridge, to enforce separation between containers, and connectivity to the physical network.

Creating a Custom Docker Network

Docker network plugins are supported by the LibNetwork project, and can be found on the docker store or other third party sites. We can also write our own custom network plugins, following the Docker plugin API and network plugin protocol. See the docker documentation for more information.

Wrapping Up

In summary, docker containers can be pulled from a docker repository, created, and run using

docker run -d \

-p <host_port>:<container_port> \

--name <container_name> \

--net <network_name>

or by writing and running a dockerfile.

Additional configuration parameters can also be found in the documentation page for that specific docker image on its DockerHub page, or its private repository documentation (if any).

The specified docker network can be created using the docker network create command, and specifying the desired network driver to be used.

As always, remember to check the official docker documentation for more information.