Intro to RL: Environments, Agents and Heuristics

Published:

Reinforcement Learning (RL) is a subtopic in Artificial Intelligence, which uses a more organic learning approach. It is vastly different from traditional Machine Learning and Deep Learning, which are dependent on swaths of highly prepared data. In contrast, RL models learn primarily through simulation and experience, much like humans. This article covers the very basic concepts used across RL topics.

Setting the Stage

Agents

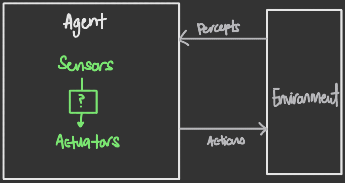

An agent is an entity that perceives its environment through some sensor(s) (LiDARs, infrared range finders etc.), and acts upon the environment through actuators (robotic legs, claws etc.).

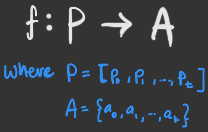

A rational agent is one that selects actions to maximise its expected utility. It can be defined by an agent function that maps a sequence of percept vectors P to an action a from set A:

Here, percepts refer to some observation of the state space of the environment (i.e. location, door open/close), and actions refer to the actions the agent can take to change the environment’s current state (i.e. move locations, open/close the door).

Rationality

A rational agent is one that is able to select the appropriate action given its environment’s state. however, what is the ‘right action’? Deciding what is the right thing to do is often a subjective opinion, often informed by a specific goal.

In modelling an agent, there must some measure of success in which we can evaluate the program’s ability to determine the best actions. This performance measure is subject to the task, and the metric should be something objective and measurable, and based on a desired environment state (not based on desired agent behaviour!). This evaluation method forms the basis of what is commonly referred to as a reward function. It is important to craft a suitable reward function for the task, as it will change an agent’s behaviour.

Rationality for agents can thus be summarised:

What is rational at a given time is dependant on:

- Performance measure

- Prior environment knowledge

- Actions

- Percept sequence to date

A rational agent chooses actions that maximise the expected value of a performance measure, given a percept sequence and environment state information.

Limits of Rationality

Ideally, an agent successfully maximizes its performance. However, this is often impossible in real-world application due to several limitations. These may be in the form of incomplete information required by the agent, or an agent’s actions leading to unexpected changes in the environment (no human or robot can predict the future after all).

We are limited by the rules and uncertainties of our physical world. Thus, in practical application, we aim for a bounded rationality based on expected performance, taking into account our limitations.

Action Space

The action space is the set of all possible actions the agent can perform in its environment. The action space can be discrete (in the case of a video game character with scripted actions and interactions), or continuous (in the case of a human agent, with infinite possible actions).

Environments

In any RL system, the environment is a pivotal part of allowing the model to learn. Just as how a well equipped nursery teaches human babies to crawl and play far more effectively than an empty room, a well designed environment can facilitate, and expedite, the successful learning of an AI model.

The environment can be defined as a structured space which an AI inhabits, and is able to take on various states that are relevant to the goal of the AI system. This environment may refer to a simulation space, or a determined space in the real world (e.g. a room with specific features and objects).

PEAS

An environment can determine the outcome of a rational agent’s learning. The features of an environment can be described according to the PEAS framework:

- Performance measure

- Environment

- Actuators

- Sensors

In the example of a packing robot in a factory’s assembly line:

- Performance measure: % Items correctly packed

- Environment: Conveyor belt, bins

- Actuators: Robot arm/hand/claw

- Sensors: Camera

Types of Environments

Environments can be categorized into types based on certain features:

- Fully or Partially Observable

- Stochastic or Deterministic or Strategic

- Episodic or Sequential

- Static or Dynamic or Semi-dynamic

- Discrete or Continuous

- Single or Multi-Agent

The criteria of these categories are as follows:

| Type | Definition |

|---|---|

| Fully Observable | The agent is able to sense the complete state of its environment at every point in time |

| Partially Observable | The agent is able to sense only some parts of the environment’s state at any point in time. |

| Stochastic | Each state of the environment is determined (in some capacity) by the passage of time. |

| Deterministic | The next state of the environment is completely determined by the current state + agent’s current action. |

| Strategic | A deterministic environment with other agents present (other agents may not be deterministic) |

| Episodic | The agent’s experience is divided into isolated ‘episodes’, where each action is only dependent on the current state of the environment, and does not account previous actions and states. |

| Sequential | The agent’s experience of the environment is affected by preceding experiences. |

| Static | The environment can only be changed via the actions of the agent, and remains unchanged while the agent considers it’s actions. |

| Dynamic | The environment may change without action of the agent. |

| Semi-dynamic | The environment does not change with external factors, but the agent’s performance score does. (e.g. in tasks where the agent’s speed matters) |

| Discrete | There is a limited number of percepts and actions, and they are clearly defined. |

| Continuous | Percepts and actions are open-ended and up to an agent’s creativity. There are no clearly defined or limited number of percepts or actions. |

| Single-Agent | A single agent operating in an environment. |

| Multi-Agent | Multiple agents operating in the same environment simultaneously. |

For example, the real world is mostly a partially observable, stochastic, sequential, dynamic, continuous and multi-agent environment. (It is also a very difficult one.)

Observation Space

There are 2 types of information that can be obtained about the environment:

- State: A complete description of the environment. No information is hidden. This is the set of information of the fully observable environment.

- Observation: Information of the visible part of the environment. This implies a partially observable environment.

Often, these terms may be used interchangeably (especially if the environment type is explicitly known).

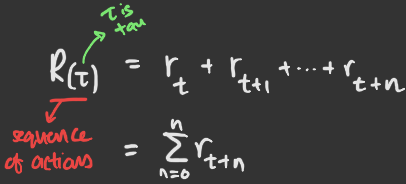

Rewards

The reward is a fundamental concept in RL, providing agents in an environment with positive or negative feedback with each action it makes. This allows the agent to learn what actions were good or bad. Agents work to maximize its cumulative reward, which determines how the agent learns to behave within it’s environment to achieve its goals.

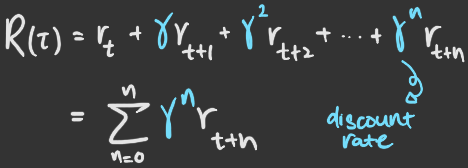

Discounting

Discounting rewards is a tactic employed in designing the reward function. This involves adding a discount rate (γ) of value between 0 and 1, as a means of adjusting the reward values, which consequently changes the priority of actions. The larger the γ value, the smaller the discount. By convention, the discount rate is usually around 0.9.

The expected cumulative reward is discounted to account for the fact that rewards that come in early stages of learning are more probable, since they are more predictable than long-term future rewards.

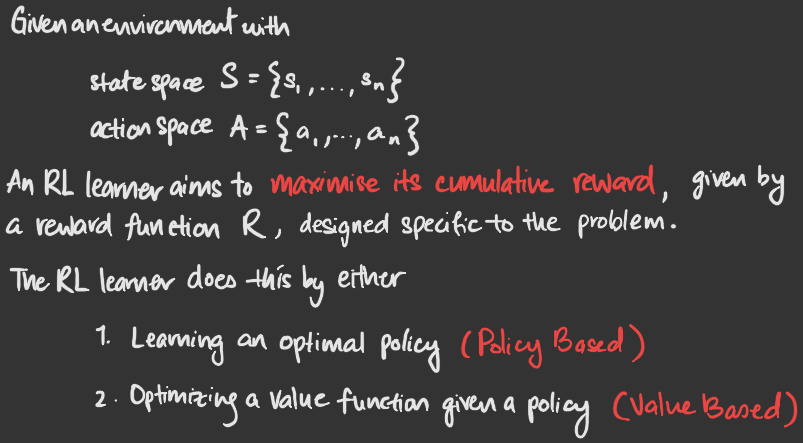

Policy

The policy (π) is a function that the RL system tries to learn. Intuitively, it is like the brain of the AI agent, which assesses the known state space and chooses an action to be executed. The goal of the RL system is to find the optimal policy (π*) through training, which is the policy that maximizes the expected reward.

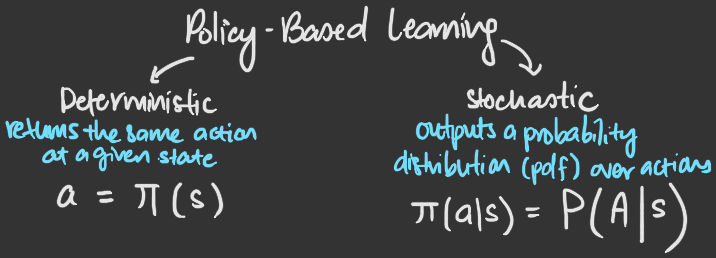

There are 2 methods of learning the optimal policy: Policy-based and Value-based methods.

Policy-Based Learning

Policy-based methods learn a policy function directly either by defining a mapping from each state to the best corresponding action, or by defining a probability distribution over the set of possible actions at each state. Hence, there are 2 types of policies:

- Deterministic: Always returns the same action given the same input state

- Stochastic: Outputs a probability distribution over actions given an input state

Policy-based learning automatically defines a policy during training, and the result of the policy is dependant on its training. We do not have to manually define what the policy is.

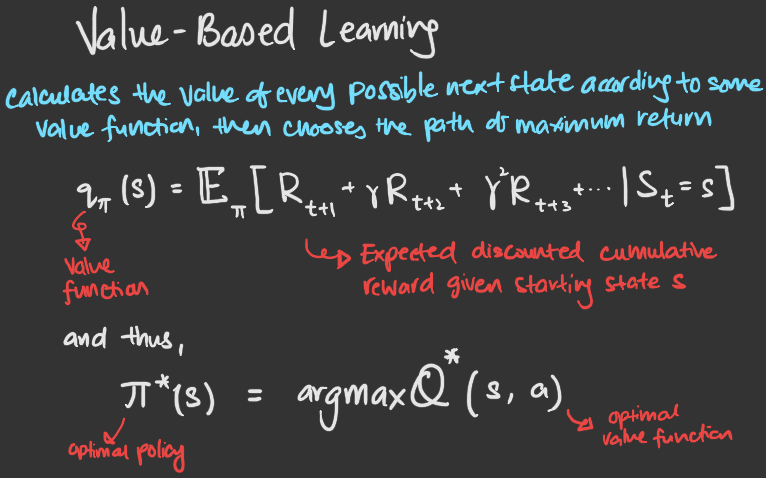

Value-Based Learning

Value-based learners learn a value function instead of a policy function. This value function maps a state to the expected value of being at that state. The value of a state is the expected discounted reward the agent will get if it starts in that state, and consequently acts to move towards a state with the highest value.

Value-based learners train a value function, which outputs the state or a state-action pair. The policy is a pre-defined (by you) function, and the value function to be trained could be a neural network. Finding an optimal value function leads to finding the optimal policy.

Designing RL Systems

Most RL systems can be represented as a graph of environment states, with edges that define the transition conditions from one state to another.

Problem Formulation

In formulating the problem, there are several parameters that should be considered. They can be summarised in the following template:

- State Space : Observed environment information

- Initial State : Initial environment information

- Actions

- Transition Model: Set of actions that can be taken at the current state

- Path Cost

- Goal Test: Goal state. Can be defined explicitly or implicitly.

There are various considerations in formulating the problem, such as choosing an appropriate representation for the states, actions, transition model and path cost. The complexity of a state space depends on its representation, and its transition model defines how the graph of states and their relationships is structured, which consequently affects the speed and method of traversing this graph.

Selecting a State Space

In problems which involve applying a model to the real world, using the real world itself as the state space creates an incredibly complex problem which is difficult to solve. Thus, the state space is abstracted and simplified for problem solving.

An abstract state may be a set of real states, and an abstract action may consist of a complex combination or real actions. For example, the action may be to move from town A to town B. In reality, this action may include the complex combination of alternative routes, detours, road blocks, and any other smaller factors and events that occur on the road from town A to B. An abstraction is valid if the path between two states can be reflected in the non-abstracted state space.

With an abstract state and abstract action, there will thus be an abstract solution. This is the set of real paths that are solutions in the non-abstracted state space.

Heuristics

When constructing a problem targeting some real world problem, you may find that the state space becomes incredibly complex due to the complex nature of the real world. In this case, you may simplify the problem by defining heuristics. For example, setting some assumptions or adding/removing rules to the system. This is known as solving a relaxed problem. Alternatively, you can instead select a smaller part of the problem to solve first, which is known as a sub-problem.

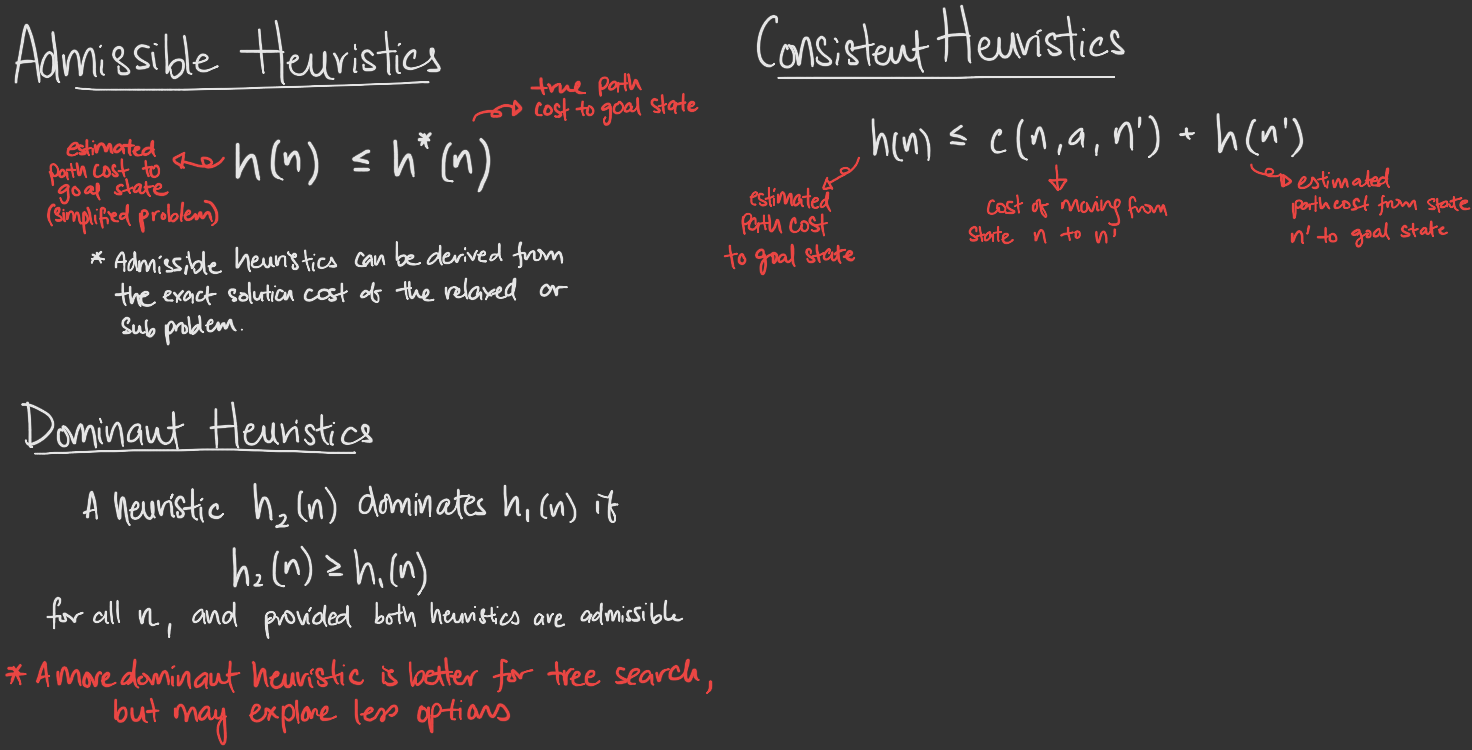

Under this simplified problem, the path cost of your problem also changes. Heuristics can have 3 properties: Admissible, Consistent and Dominant.

In general, heuristics are often used with informed and uninformed search algorithms.

Exploration-Exploitation Trade-off

In any RL system, the goal of the agent is to maximize its expected cumulative reward. The way an agent performs it’s task of finding the best actions to take can be summarized as:

- Exploration: The process of learning more about the environment by trying random actions and recieving feedback

- Exploitation: Making use of known information to maximize the reward

In the exploration-exploitation trade-off, an agent that repeats an action known to give a positive reward (exploitation) may miss out on trying new actions which may or may not yield bigger rewards (exploration).

The degree of exploration and exploitation must be balanced for the agent to learn about its environment appropriately. To prevent an agent being stuck at one end of the spectrum, a rule must be defined to handle this trade-off.

Putting it All Together

In this article, I review the basic concepts of an RL problem, and introduce the problem forming heuristics in designing the RL problem. Let’s summarize with an example.

Example: Cat and Mouse Game

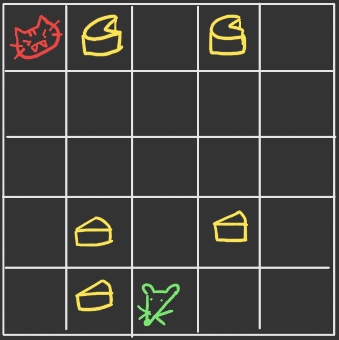

Imagine a board game where you, the mouse, has to get as much cheese as possible while avoiding the cat. In this turn based game, you and the cat take turns to move to 1 adjacent square. The initial board state begins with small blocks of cheese (+1 point) around the mouse, and larger cheese wheels (+50 points) near the cat. Cheese pieces respawn at the same location every 2 turns.

The win and lose conditions are:

- Mouse wins if it collects a total of 100 points

- Mouse loses if it gets caught by the cat

Assessing the Environment

Here, the environment has the following features:

- Fully Observable: The full board state is visible to all players at all time

- Multi-agent: Cat AI and Mouse AI

- Static: The board state does not change until the mouse makes a move

- Strategic: The game state is deterministic based on the mouse’s actions, but with other agents present

- Sequential: The changes in state depends on where the mouse moves to

- Discrete: The mouse has at most 4 possible actions (move left, right, up or down)

Problem Formulation

The problem can be formulated as:

- State Space: [array of position of all pieces on board]

- Initial State: [array of initial board configuration]

- Actions

- Transition Model: Xi,j -> Xi±1, j±1

- Path Cost: Point value of cheese (if any)

- Goal Test: Check if mouse has 100 points

Exploration-Exploitation: Infinite small cheese or Instant Win Big Cheese

Since the cheese respawns every few turns, we have 2 general strategies for maximising our goal:

- Exploit the infinite respawning small cheese near the mouse in the initial board configuration and ignore the risky big cheese near the cat

- Explore the board and find the big cheese

Given the greater risk involved in finding the big cheese, and the lack of penalty for exploiting the small cheese (i.e. no penalty for being slow or taking more turns to reach the goal), the model is likely to fall into an exploitative cycle of being stuck at the bottom of the board with a pile of small cheese.

But, this is boring behaviour.

Reward Function

The goal of the mouse AI is to maximize its points by collecting cheese. Thus, the cumulative reward function can be defined simply as a sum of accumulated rewards (points from cheese) at each turn.

However, since we don’t want to encourage the mouse’s exploitative behaviour, we discount the reward by introducing a discount rate term to the reward function.

Recall that the discount rate is a value between 0 and 1. This means that the discount rate decreases as the number of turns increase, and thus future turs later in the game are more heavily penalised. The reward gained from collecting the small cheese near the mouse at the start of the game becomes so small that the mouse is encouraged to explore the board more.

note: example adapted from HuggingFace’s Deep RL Course

Summary

An overview of a reinforcement learning system can thus be said to be

Links and Resources